Alveoli

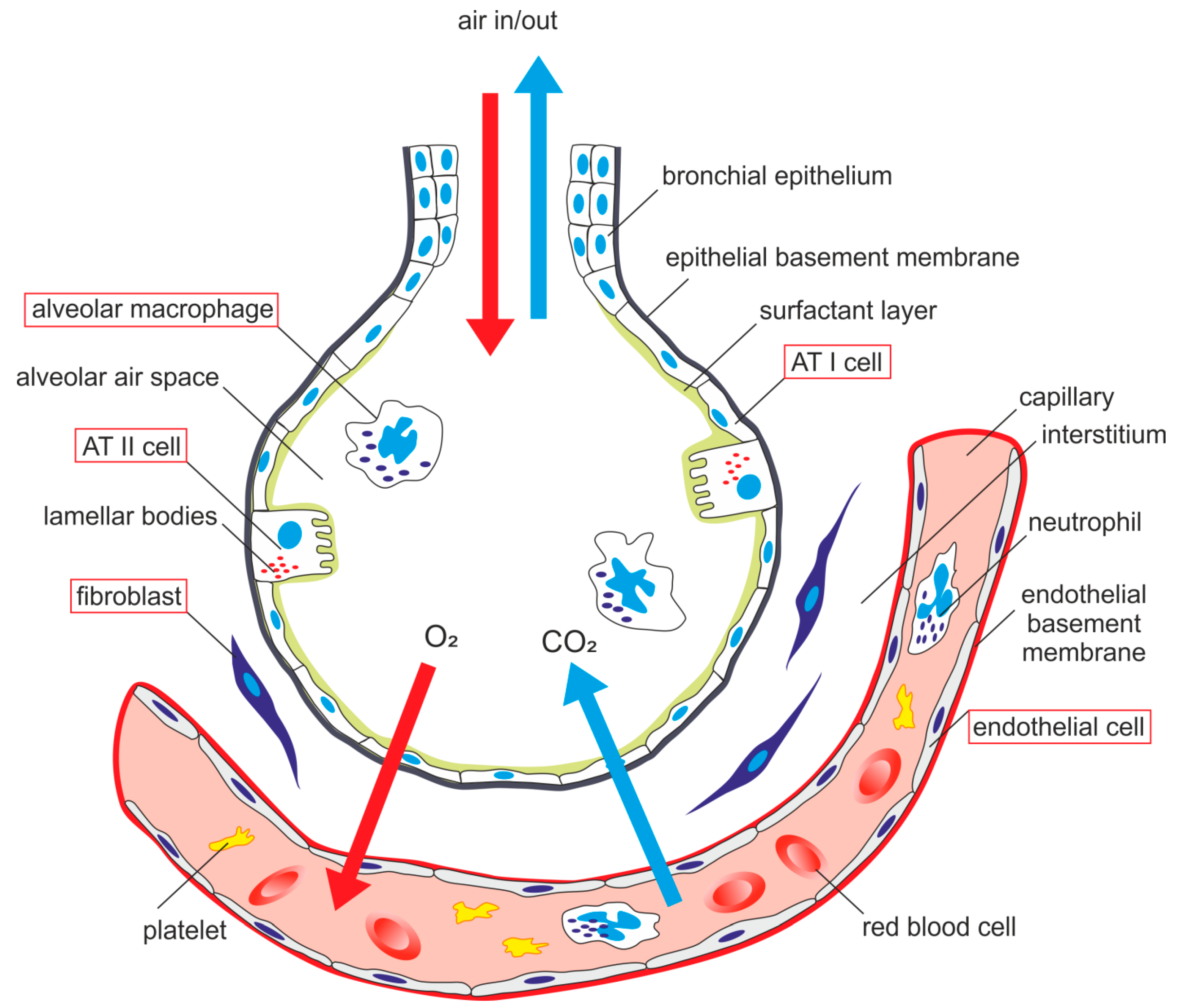

The alveoli are small, air-filled, saclike structures that make up most of the lung structure. They are the sites of the exchange of O2 and CO2 between inspired air and the adjacent pulmonary capillaries

These alveoli are lined by flattened epithelial cells called pneumocytes with a single opening. The alveolar wall or septum is made up of three tissue components: surface epithelium, supporting tissue, and an extensive network of continuous capillaries. Centrally it has capillaries surrounded by a vibrant network of elastin, reticular, and collagen fibers with a layer of squamous epithelial of two adjacent alveoli on either side.

Hence air in alveoli is separated from the blood in the capillary by three components, surface lining and cytoplasm of alveolar cells, fused basal laminae of closely apposed alveolar, and endothelial cells and their cytoplasm. This is called the blood-gas barrier (air blood barrier). Capillaries are continuous with its endothelial cells, which are extremely thin due to the clustering of nuclei and other organelles, increasing the efficiency of exchange. Occasionally small openings, alveolar pores (of Kohn) (10-15µm in diameter) are seen which equalize air pressure within alveoli and allow air movement between alveoli in case of the bronchiole obstruction. Elastic fibers enable alveoli to expand during inspiration and contract passively during expiration. The reticular fibers serve as supportive structures that prevent over-distention and damage to delicate capillaries and alveolar septa. Two types of epithelia form a continuous lining around each alveolus. They are type I pneumocytes (alveolar lining cells) and type II pneumocytes.1

Type I Pneumocytes (Alveolar lining cells)

The type I Pneumocytes are simple squamous cells that are highly attenuated with a dense, small, and flattened nucleus. These cover most of the surface area, approximating around 95-97% of the total surface area. Golgi complex, endoplasmic reticulum, and mitochondria are grouped around the nucleus, leaving a large area of cytoplasm free of organelles, thus reducing it to a fragile blood-air diffusion barrier (25nm). The thin cytoplasm shows numerous pinocytotic vesicles. The surfactant lines the luminal surface. A basal lamina covers the adluminal side of these cells. The adjacent cells are connected by tight (occluding) junctions, which prevent leakage of tissue fluid into the alveolar lumen. During fetal development, the surfactant appears in the last few weeks of gestation and coincides with the appearance of lamellar bodies in the type II cells.

Type II Pneumocytes (Great alveolar or septal cells)

The type II Pneumocytes are the cuboidal cells grouped in 2-3, large, a central, and plump nucleus with dispersed chromatin and prominent nucleoli. They occupy about 3-5% of the surface area of alveoli interspersed among type I cells with which they have occluding and desmosomal junctions. The apical surface is dome-shaped and shows numerous small microvilli associated with surfactant secretion. These type II pneumocytes secrete Surfactant, a surface-active material that reduces surface tension, thus preventing alveolar collapse during expiration. The mitotic activity of the lining cells is 1% per day and can differentiate to type II, as well as type I pneumocytes in response to damage to alveolar lining epithelium. The cytoplasm has abundant rough endoplasmic reticulum, well developed Golgi apparatus, free ribosomes, and a moderate amount of elongated mitochondria. A typical feature of these cells is the presence of lamellar bodies. These lamellar bodies are vesicles containing phospholipid (dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine) (1-2µm). These, when discharged by exocytosis into alveoli, spreads on alveolar surface and combines with other carbohydrate and protein-containing secretory products (some secreted by Clara cells) to form surfactant, which is a tubular lattice of lipoprotein known as tubular myelin, which overcomes effects of surface tension. The reduction of surface tension means a reduction of work of breathing. The surfactant is not static but continually being turned over and removed. The removal is by pinocytotic vesicles of type II pneumocytes, macrophages, and type I pneumocytes.

Alveolar Macrophage (Dust cells):

The alveolar macrophages are derived from blood monocytes and sometimes by mitotic division of macrophages of the lung. They contain numerous secondary lysosomes and lipid droplets. They phagocyte and remove unwanted materials such as inhaled particulate matter (carbon), dust, and bacteria. They are present free within alveolar spaces and some in inter-alveolar septa (spaces). One hundred million macrophages daily migrate to bronchi. The phagocytosed macrophages get trapped in mucus, transported by ciliary action to the pharynx, and come out in sputum. Some alveolar macrophages also go via lymphatics to hilar lymph nodes. Industrial lung disease like silicosis is because of inhalation of silica into air sacs (as tiny particles) that are phagocytosed by macrophages. Silicated macrophages stay for a long time and convert silica into silicic acid, which stimulates the proliferation of fibroblasts and collagen, leading to fibrosis of lung and node. A particular form of silica, like asbestos, when inhaled extensively stimulates lung fibrosis producing asbestosis and sometimes malignancy of pleura (mesothelioma). Sometimes macrophages phagocytose extravasated RBCs in alveoli (especially in conditions like pulmonary congestion and congestive heart failure). These erythrocyte phagocytosed macrophages are called heart failure cells.

References

1. Khan YS, Lynch DT. Histology, Lung. [Updated 2023 May 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534789/

The pores of Kohn (also known as interalveolar connections or alveolar pores) are discrete holes in walls of adjacent alveoli.[1] Cuboidal type II alveolar cells, which produce surfactant, usually form part of aperture.

Reference

https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/20/4/831/htm

At the end of a deep breath, about 80% of the lung volume is air, 10% is blood, and only the remaining 10% is tissue. Because this small mass of tissue is spread over an enormous area

Type I alveolar cells (pneumocytes)

Type I alveolar cells (pneumocytes) are membranous pneumocytes that comprise 95% of the single-layered alveolar wall. These cells are extremely thin, simple, squamous epithelial cells that can no longer divide. Their luminal surfaces face the air space; their function is to participate in gas exchange across the alveolar-capillary membrane.

Type II alveolar cells (pneumocytes) are cuboidal cells that comprise the remaining 5% of the single-layered alveolar wall. These cells have two critical function

-

They are the regenerative cells of the lung . When lung damage occurs, these cells proliferate and have the ability to regenerate type I cells .

- ●

Type II alveolar cells also contain foamy vesicles called lamellar bodies, which continuously produce pulmonary surfactant that covers the luminal surface of the alveoli.

- ●

Surfactant is a protein-lipid material that reduces surface tension on the surface of the alveoli so they can expand more easily during inspiration. The main lipid component of surfactant is dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine. It is important to know that lamellar bodies begin to appear in the last few weeks of gestation and that fetal production of corticosteroids is important in inducing surfactant production. Thus, premature neonates may experience respiratory distress if the mother is not given corticosteroids prior to delivery to help increase surfactant production.

Lymphatics???